How to Self-Critique and Self-Edit Your Humor Writing

And why is self-critique so hard to being with?

Quick PSA - New Writing Groups: Writing groups are back on the menu. If you’re an annual paid subscriber to Comedy Bizarre, and you want me to put you in a humor writing group in January 2025, there’s a Google Form link at the end of this post, behind the paywall. Be sure to fill it out!

“My question: how do you get better at editing and critiquing your own work, outside of reading a lot of funny stuff and practicing editing your own? A writing group, I'm thinking, but anything else?” - Matt H.

No bones about it: Self-editing is hard. Sometimes it’s super hard. Why?

I think the difficulty starts with what linguist and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls "the knowledge problem” of writing. The challenge, as he lays it out, is oriented slightly more at nonfiction writing, but I’d argue it plagues all writers.

The knowledge problem is the challenge writers face when they assume their readers know as much as they do. It leads writers to leave out essential background info, to not explain their concepts clearly, and to generally leave their readers in the dust. We too easily forget what it’s like not to know something. The knowledge problem is especially thorny in academic and technical nonfiction writing.

You can read more about that in Pinker’s book A Sense of Style, which I enjoyed.

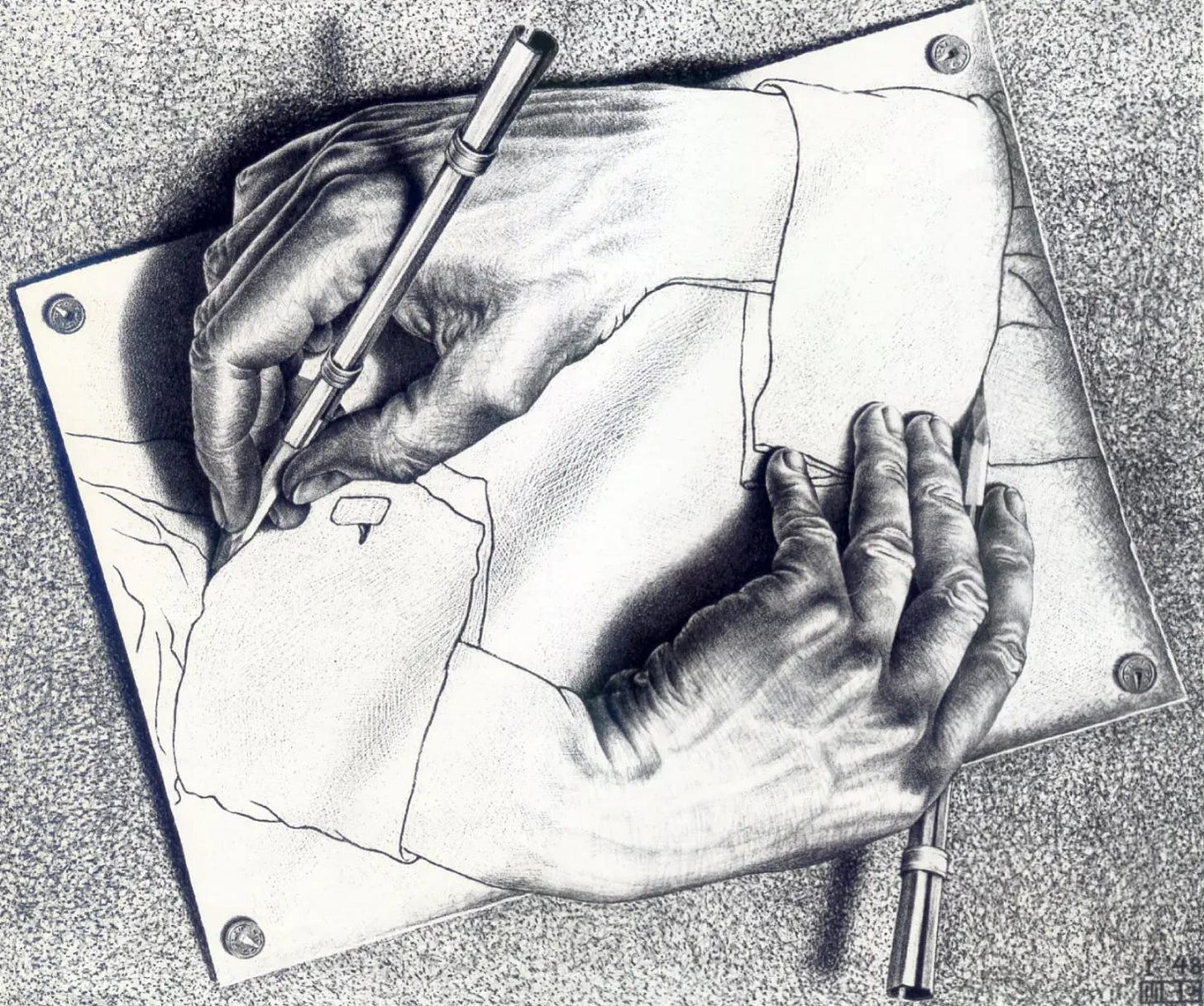

In fiction and creative writing, the situation is a bit different since we’re less focused on trying to teach or convince our readers of something—other than our own cleverness, womp womp. But the knowledge problem is still there in an essential way. And I think this comes down to the fact that, as a writer, it’s really hard to step outside your own head. It’s hard to write in a way that just transparently shows the reader what you're up to or what you’re trying to do. We’re stuck forever inside the veil of our thoughts.

Creative and fiction writers run into the knowledge problem when they perfectly understand some clever story or joke or imaginative premise in their mind but they can’t make it coherent on paper. The reader goes, “Wait, what are you doing here? What’s going on?” And the writer goes, “But yo, in my head, this SLAMS.”

With that in mind, my experience is that your ability to self-edit takes a quantum leap when you can honestly and skillfully answer two questions:

If this draft had been written by someone else, and I were critiquing and editing it, what criticisms and edits would I make?

If one of my writing group friends were to critique this draft, what would they say?

(Note on question 2: I think it can be extra helpful to actually answer this question by stepping into the shoes of a specific critique partner you know well. Forget about what Generic Writing Group Person would say. What would Lindsay The Genius say?)

Anyway, the hard part about these two questions is answering them honestly and skillfully.

First, honesty. These questions are hard to answer honestly because it’s hard to get objective distance from our own writing. I imagine it’s about as hard as being objectively honest about the beauty and intelligence of your own children. We all want very badly for our writing to be brilliant. We cling to our ideas and our sentences like they are shiny, little gifts from God. Honesty requires depersonalizing things, detaching the writing from our identity. That’s hard, man.

Second, skill. It’s hard to answer these questions skillfully when you lack the hard-won skills of an editor or of a thoughtful critique partner. It takes editing and critique experience to get better at editing and critique. If you’re not experienced at editing, why think you’d be any good at self-editing—which is like editing plus emotional baggage?